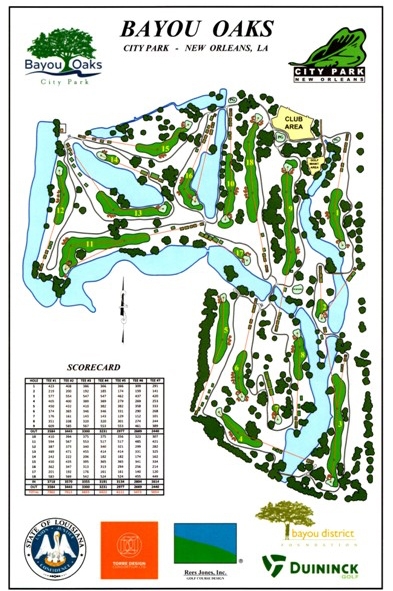

The new Bayou Oaks at City Park South golf course designed by Rees Jones opened April 21st, 2017. There are two courses named the South Course and North Course also include a driving range, ancillary short-game facility and two clubhouses.

With unbridled enthusiasm, Jonathan Ashford arranged nine plastic foam cups around the rug of the Columbia Parc community center and sank putts on his makeshift course as if his dinner that night depended on it.

A day earlier, Jonathan, 9, and his friends in the First Tee of Greater New Orleans, a program that introduces young people to golf, played three holes on the South Course at Bayou Oaks. It is a public golf facility that opened on April 21, several hundred yards from where Jonathan and his mother live. His days of having to putt into coffee cups are numbered.

“It’s like having a golf course in your backyard,” said Claudette Ashford, Jonathan’s mother.

To create the South Course, the renowned architect Rees Jones took two City Park courses left in ruins by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and built an 18-hole layout that is expected to garner the same cachet among golfers as two of his previous municipal courses, Torrey Pines and Bethpage Black, which have hosted the United States Open.

The third hole sits not far from Columbia Parc, a housing development in the Seventh Ward that was built through a public-private partnership after the blighted St. Bernard public housing complex had been demolished. The Columbia Parc project, which includes mixed-income residences and other community assets, has been hailed as a way to revitalize a neighborhood. It has also been criticized for displacing many residents of St. Bernard.

South Course at Bayou Oaks

Golfers at the South Course at Bayou Oaks. About $500,000 annually from golf operations will help support community programs, and another $800,000 will go toward activities at the park were Bayou Oaks is located. (Credit Edmund D. Fountain for The New York Times)

Golfers at the South Course at Bayou Oaks. About $500,000 annually from golf operations will help support community programs, and another $800,000 will go toward activities at the park were Bayou Oaks is located. (Credit Edmund D. Fountain for The New York Times)

It all began with an email.

Shortly after Hurricane Katrina decimated New Orleans in August 2005, Charlie Yates Jr. – an Atlanta philanthropist and an executive at the time for Zurich Insurance Group, title sponsor of the PGA Tour stop in New Orleans – reached out to Mike Rodrigue, a former tournament chairman of the Zurich Classic. Yates invited Rodrigue to bring a group to see the urban revitalization project nested next to East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta, the home course for Bobby Jones, the first golfer to complete golf’s Grand Slam, in 1930.

A few months later, Rodrigue toured East Lake’s surrounding community with Gerry Barousse Jr., a real estate developer and banker, and Gary Solomon, a venture capitalist. They marveled at the effort, which was spearheaded by Tom Cousins, a real estate developer who built the CNN Center and helped bring N.B.A. and N.H.L. teams to Atlanta.

In 1995, Cousins bought East Lake Golf Club out of receivership and established the East Lake Foundation. He partnered with the City of Atlanta to raze East Lake Meadows, a troubled 650-unit public housing complex, and build the Villages of East Lake, a mixed-income community. A charter school, a Y.M.C.A. and a nine-hole public golf course soon followed.

Proceeds from hosting the Tour Championship at East Lake Golf Club are funneled back to the foundation for community programs. The effect on the neighborhood can be measured in a drastic reduction in crime, high employment rates, and improved academic scores and high school graduation rates.

On the trip home to New Orleans, Rodrigue’s group debated whether the East Lake model could be replicated in New Orleans.

A larger debate brewed over the future of public housing in New Orleans, a subject fraught with charges of gentrification and discrimination. Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans had more than 7,000 public housing units.

Rodrigue grew up in Gentilly, a neighborhood that was a half a mile north of the St. Bernard projects, and recognized the similarities to the East Lake project. His parents forbade him from stepping foot in St. Bernard, one of the most dangerous areas in the city. Instead, he was dropped off every day at City Park, the 1,300-acre park just to the west of St. Bernard, and he played golf.

Read more by Adam Schupak at NewYorkTimes.com