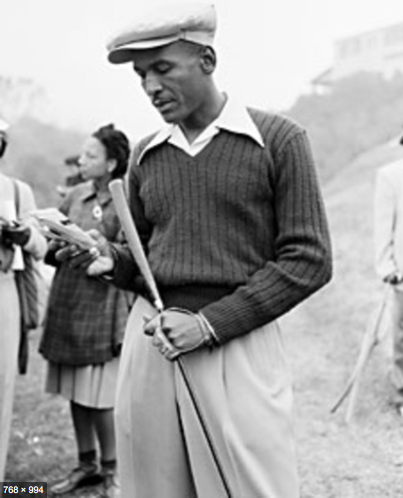

Bill Spiller, Born: October 25, 1913, Tishomingo, Oklahoma, United States Died: 1988, Los Angeles, California, United States

Born in Tishomingo, OK, Spiller moved to Tulsa as a nine-year-old to live with his father where he quickly learned the drawbacks of being black in America. One day, he went to a store to return some merchandise he had bought. A white sales clerk slapped Bill for what he claimed was impudence. It so angered Bill that he raced home, got a gun, strapped it on and wore it until his sophomore year at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas. Spiller wore his indignation about race on his sleeve. He was also an excellent athlete, a two-sport star in high school.

However, golf was not one of them. He didn’t take up the game in earnest until he was almost 30, but quickly became one of the top black players in Southern California, where he had moved to live with his mother after earning enough college credits to obtain a teaching certificate in the state of Texas. He pieced together a game based on the swings of his favorite PGA Tour stars. By the mid-1940s, Spiller had won several black amateur tournaments in Southern California and felt ready for bigger challenges. He played against the best African American players in the Joe Louis Invitational at Rackham GC in Detroit and the nation’s best pros in the Los Angeles Open and Tam O’Shanter in Chicago, two PGA Tour events open to Blacks.

He befriended several white players, including Lawson Little and Jimmy Demaret who helped convince CC president George S. May to invite black players to his tournament. In 1947, Spiller turned pro and toured the UGA with Louis, among others. The competition forced him to take a reality check. One day Spiller hustled Louis out of $7,000 in a showdown that started at dawn and didn’t conclude until it was too dark for the pair to see each other. He bought a small house with his winnings. Peace of mind, however, would prove more expensive and elusive. Spiller desperately sought to earn a living playing golf professionally and that meant eschewing the paltry purses of the black golf tour for the more lucrative PGA circuit.

Only one thing stood in his way; the PGA’s exclusionary Caucasian-only clause. Spiller shot a 68 to tie Ben Hogan for second place after the first round of the Los Angeles Open at the Riviera Country Club in 1948. Although he faltered and eventually finished 20 shots behind the victorious Hogan, Spiller finished in the top 60, making him eligible for the next PGA tournament, the Richmond Open outside Oakland.

However, when he showed up to play, PGA Tour official George Schneiter enforced the Caucasian-only clause and turned them away. It wasn’t until four years later that Spiller and his fellow outcasts, led by Louis, were able to deliver the first effective blow to the PGA and its policy.

It came at the San Diego Open, where tour officials refused entry to Spiller and another African American pro named Eural Clark. Louis was allowed to play after the PGA was the subject of several critical reports by Walter Winchell in a national radio broadcast that exposed the tour’s racial bias even toward a war veteran. Louis’ tenacity forced a vote later that week by the PGA Tournament Committee that resulted in a rule change. Essentially, African Americans could not be kept out of a tournament if they received one of the 10 sponsor exemptions or earned one of 10 spots in the field through open qualifying. However, the association refused to budge on the matter of allowing them to hold PGA Tour membership. Spiller’s lack of success in the PGA Tour events in which he was allowed to compete (his best finish was a 14th place at the Labatt Open in Canada) forced him to turn to other means of supporting his family. He hustled golf lessons and caddied at Hillcrest Country Club. That hurt him collectively more than anything else.

Later in life, when confined to a convalescent home after suffering two strokes and being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Spiller would clutch the faded newspaper clippings detailing his protests in the clubhouses and exploits on the course. Bill Spiller died in 1988.

Article by Dianne Washington