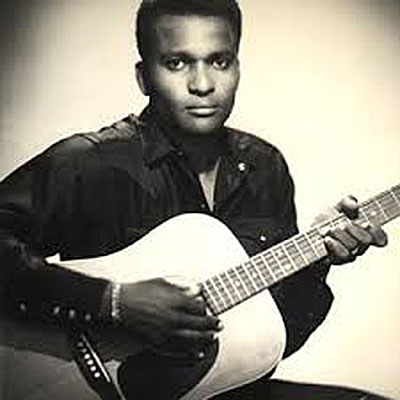

Charley Pride — a sharecropper’s son who rose from rural Mississippi to become the first Black superstar in country music — died Saturday at age 86.

The “Kiss An Angel Good “Mornin” singer died in Dallas, Texas, due to complications from COVID-19, according to a news release from his publicist, Jeremy Westby. In a career spanning more than five decades, Pride cemented a trailblazing legacy unlike any entertainer before him.

He overcame club audiences unwilling to hear a Black singer cover Hank Williams and promoters equally skeptical at hosting his performances to once being the best-selling artist on RCA Records since Elvis Presley.

Pride topped country charts 29 times in his career, singing stories rich with honesty — “I Can’t Believe That You’ve Stopped Loving Me,” “I’m Just Me” and “Where Do I Put Her Memory,” among others — in his distinct, welcoming baritone voice.

Though he detailed his struggles in his 1995 autobiography, Pride wasn’t always one to dwell publicly on the magnitude of his accomplishments. As he spoke to The Tennessean in November, he said he was often asked which of his songs was his favorite to sing.

His response? “The one that I’m singing at the moment. Out of 500 and some songs, that’s what my answer is.”

Pride’s vast accolades include Country Music Association Entertainer of the Year in 1971, Male Vocalist of the Year wins in 1973 and ’74 and a 1993 invitation to join the Grand Ole Opry.

And, in 2000, he became the first Black member of the Country Music Hall of Fame.

“To be doing that at a time when nobody really wanted him here, it’s crazy to look back now … that must’ve been so hard,” Darius Rucker told The Tennessean in November. “I can deal with whatever comes my way because it can’t be near what Charley went through.”

His remarkable career was applauded by a live audience at last month’s CMA Awards, where he received the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award. He was introduced by one of the genre’s modern Black stars, Jimmie Allen.

“I might never have had a career in country music if it wasn’t for a truly groundbreaking artist, who took his best shot, and made the best kind of history in our genre,” Allen told him.

Unlike nearly every other awards show held this year, the CMAs were produced with a live, socially distanced audience at Nashville’s Music City Center.

Mississippi upbringing

Charley Frank Pride was born to father Mack Pride and mother Tessie B. Stewart Pride on March 18, 1934, in Sledge, Mississippi. One of 11 children, he worked as a kid picking cotton for his father, a local sharecropper who often gathered his family around an old Philco radio to play Grand Ole Opry broadcasts.

Pride saved $10 to buy his first guitar, with an assist from his mother, out of a Sears Roebuck catalog.

He learned songs from formative Opry singers, often hearing the Louvin Brothers on the famed WSM broadcast — which, at 50,000 watts, traveled 275 miles southwest to Pride’s corner of rural Mississippi — and catching radio star Smilin’ Eddie Hill at makeshift concerts in town.

“I lived only 54 miles from Memphis,” Pride said. “They’d come down, put a flat bed truck up.”

Pride later told Hill: “I wanted to get up there so bad. He said, ‘You shoulda said something. We would’ve probably got ya up there.’ That wasn’t the thing to do back in those days. Segregation, you know.”

But music only played a B-side in Pride’s burgeoning passions. His first big hit came on the baseball diamond.

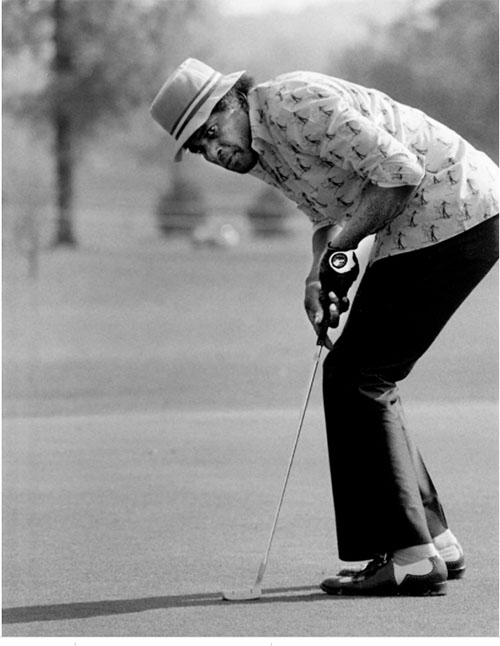

He was named along with Faron Young by Hall of Fame member Brenda Lee, right, during a press conference at the Hall. Pride was emotional just after learning he has been elected as the newest member of the Country Music Hall of Fame June 16, 2000 during Fan Fair week. He was named along with Faron Young by Hall of Fame member Brenda Lee, right, during a press conference at the hall.

In the 1950s, not a decade after Jackie Robinson smashed segregation barriers for Black athletes in the major leagues, Pride would peruse his own major league career. He bounced between Negro leagues and major league farm systems, pitching for teams in Wisconsin, Kentucky, Alabama, Idaho, Texas and, perhaps most notably, the Memphis Red Sox.

He’d earn a stop in 1956 on the Negro American League all-star team, only to be drafted later that year into U.S. military service. He served until 1958.

“I was gonna go to the major leagues and break all the records there and set new ones,” Pride said, adding a laugh. “By the time I was 35 or 36, then I was gonna go sing. That’s what my plan was.” In the early 1960s, Pride’s major league opportunities dwindled — but his voice grew.

He lived in Montana at the time, where he played semi-pro baseball, worked at a smelting factory and occasionally sang tunes in honky-tonk bars. At a Montana gig in 1962, touring country singers Red Sovine and Red Foley invited Pride to sing two songs on stage — “Lovesick Blues” and “Heartaches By The Number.”

Sovine encouraged Pride to visit Cedarwood Publishing in Nashville and, in 1963, he obliged. Pride first took to Music City on his way home from a New York Mets tryout in Clearwater, Florida.

At Cedarwood, Pride connected with his would-be manager Jack D. Johnson and, two years later, landed a deal at RCA with the help of Chet Atkins and producer “Cowboy” Jack Clement.

In the mid-1960s — as civil rights activists marched for equality in the South — the label hesitated at promoting an African-American in country music.

Despite being arguably formed by intertwining Black and white Southern cultures in the early 20th century, the once-called “hillbilly” format (“hillbilly music” was released in the 1920s as a segregated marketing tactic for white record buyers; Black consumers were marketed toward “race records”) was dominated for decades by white artists and gatekeepers.

Charley Pride wearing a suit and tie: Charley Pride gets ready to perform during the 14th annual CMA Awards show at the Grand Ole Opry House Oct. 13, 1980.© Ricky Rogers / The Tennessean Charley Pride gets ready to perform during the 14th annual CMA Awards show at the Grand Ole Opry House Oct. 13, 1980. The label pushed Pride’s early singles, such as “The Snakes Crawl at Night” and “Before I Met You,” without distributing his picture.

RCA could keep Pride’s face off a record, but promoters couldn’t keep him from audiences who paid tickets to hear his voice. Pride recalled being introduced to rousing applause early in his career, only to be greeted to silence as he took the stage. He makes a sound similar to a deflating balloon when recalling those first gigs.

“They were quiet as a pin,” Pride said. “They thought maybe it was a joke.”

During a 1966 show at Olympia Stadium in Detroit, Pride faced the biggest gig of his career to that point. He’d been walking out to a few hundred deflated balloons each night. This night, he’d be walking out to thousands.

“Here’s what Jack and I came up,” Pride said, “‘Ladies and gentlemen I realize it’s a little unique with me comin’ out on stage wearin’ this permanent tan. I got three singles — I only have ten minutes — I get through with those I’ll maybe do a Hank Williams song, but I ain’t got time to talk about pigmentation.'”

“And I hit it.”

Legacy in the song

By 1967, Pride sang his way into the top 10 of the country charts with “Just Between You and Me.” And he didn’t stop there. From the downhome honesty on “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me)” to wanderlust heartbreak on ‘Is Anybody Goin’ to San Antone,” Pride’s charming baritone propelled him to the top of country charts throughout the 1970s and ’80s.

He reached a pinnacle of commercial country music success achieved by few artists before him, totaling more than 50 top 10 country hits.

“Just as a country music singer, Charley Pride is one of the all-time greats,” Rucker said. “He’s a superstar, everybody knows he’s an icon.”

And no song may be associated with Pride’s legacy more than hit “Kiss An Angel Good Morning,” which spent five weeks at No. 1 on the country charts and crossed into pop success.

Charley Pride tries out a seat on the MTA trolley car named for him June 15, 1999. The car, with “The Pride of Country Music” emblazoned on the side, was dedicated during Pride’s annual Fan Fair breakfast.© P. Casey Daley / The Tennessean Charley Pride tries out a seat on the MTA trolley car named for him June 15, 1999. The car, with “The Pride of Country Music” emblazoned on the side, was dedicated during Pride’s annual Fan Fair breakfast.

“I had no idea it would do what it did,” Pride said. “I just couldn’t wait to get into the studio to get that baby done. It’s been my biggest, so far.”

He credits his success to the singing that took him from baseball fields to the Grand Ole Opry stage.

“Chet Atkins, he told Jack Clement he’d never heard a voice … just cut through, when I started singing like that,” Pride said. “I guess it’s the richness of the voice.”

After earning Entertainer of the Year in 1971, Pride won the CMA Awards’ Male Vocalist of the Year in 1973 and 1974 — the first artist to earn back-to-back victories in the competitive category.

A three-time Grammy Award winner, the Recording Academy honored Pride with a Lifetime Achievement award in 2017.

At his peak, some referred to Pride as the Jackie Robinson of country music, but the path for Black country singers after Pride wouldn’t be followed as quickly as those in major leagues. It took country gatekeepers until 2008 to welcome another Black artist, Rucker, to top the radio charts; pleas for diversity on the charts and in positions of power in country music continue today.

In the final year of his life, Pride’s influence and impact was perhaps more evident than ever. One of the last songs he recorded was “Why Things Happen,” a collaboration with both Allen and Rucker, as other Black country performers continued to find critical acclaim (Mickey Guyton) and chart success (Kane Brown).

As he stood on stage at the CMAs in November, Pride acknowledged that he’d been a inspiration for many others. But he immediately pivoted, dedicating almost all of his two minute speech to key figures in his life and career, including Johnson and Clement.

“With all of the people that have been influenced by my life, and what my life has been influenced by, I’ve gotta say something about some of them.”

In lieu of flowers, the Pride family asks for donations to The Pride Scholarship at Jesuit College Preparatory School or St. Philips School and Community Center in Dallas. Donations may also be made to a local food bank or a charity of choice.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Charley Pride, country music’s first Black superstar, dies at 86 of COVID-19 complications.