Delaitre Hollinger, Executive Director/CEO at National Association for the Preservation of African American History & Culture says, “They deserve much better than this.”

BY AAGD STAFF

December 30, 2019

The long-whispered gossip has finally come to light with the discovery of 40 unmarked graves on a country club in Florida. The graves have given rise to heated debate, as they have been determined to be the resting place of slaves. This land is just one of many of the south’s unmarked (former) slave cemeteries.

For decades, rumors swirled about the long, dark history of what lay beneath the grassy knolls and finely manicured lawns of Capital City Country Club located in Tallahassee, Florida’s capital city. Established in 1908 and located at 1601 Golf Terrace Drive, Tallahassee, FL 32301members enjoy an abundance of amenities and opportunities for golf and lessons along with tennis, swimming, fitness, Professional golf instruction from PGA certified golf professionals and personal training from a Titleist Performance Institute certified instructor.

It was along the 7th fairway, where, over the years, neat rows of rectangular depressions could be seen deepening in the grass, forming outlines of what would be confirmed this month as sunken graves of the slaves who lived and died on a cotton plantation.

So far, 40 graves have been discovered, however, there is speculation that there could be dozens more on the property. Now comes the conversation of how the residents of these unmarked plots should be honored on what is now a pristine golf course. Along with this discussion, revitalized attention has been bought to the thousands of unmarked and forgotten slave cemeteries across the deep south that forever could be lost to development or indifference.

“When I stand here on a cemetery for slaves, it makes me thoughtful and pensive,” said Delaitre Hollinger, the immediate past president of the Tallahassee branch of the NAACP to the Guardian.com. Hollinger explains that his ancestors were among the Leon county slaves who worked in the fields of this area. Hollinger is Executive Director/CEO at Nat’l Assoc. for the Preservation of African-American History & Culture

“They deserve much better than this,” said Hollinger, 26, who is leading a push to memorialize the rediscovered burial ground. “And they deserved much better than what occurred in that era.”

For years, golfers have unknowingly teed up, walked and played 18 holes of golf on the course which once held wooden markers that had identified the graves of this former cemetery.

During the antebellum era, Leon county was the center of Florida’s plantation economy and boosted the state’s highest concentration of slaves. Just before the civil war, three of every four county inhabitants were human chattel owned by elite white families.

One such family, the Houstouns of Tallahassee, operated a 500-acre plantation from the early 1800s through the civil war. Over the years, the land has been parceled out to developers and the fields were transformed into an expanse of commercial and residential usage, including strip malls and neighborhoods, some being very stately homes.

A huge swath of the property became the Capital City Country Club, now an 18-hole golf course in one of Tallahassee’s most sought-after communities.

“It’s fair to say that the golf course is one of the reasons why this burial ground has been preserved as well as it has for so long,“ said Jay Revell to The Guardian.com. Revell is the country club’s resident historian and the vice-president of the region’s chamber of commerce.

“A hundred years ago when the golf course was constructed there was certainly no technology to decipher what was or wasn’t here,“ he said during a recent visit to the country club.

Area old-timers had long been talking about the remains of the long-gone plantation and this cemetery.

The stories piqued Hollinger’s curiosity and he pursued the rumors, digging into newspaper archives, where he found clippings dating back to the 1970s that mentioned the burial site.

Hollinger then made contact with Tallahassee city officials and asked for assistance, who in turn reached out to experts, including the National Park Service.

The effort gained the involvement of a park service archaeologist, Jeffrey Shanks, who took up the cause.

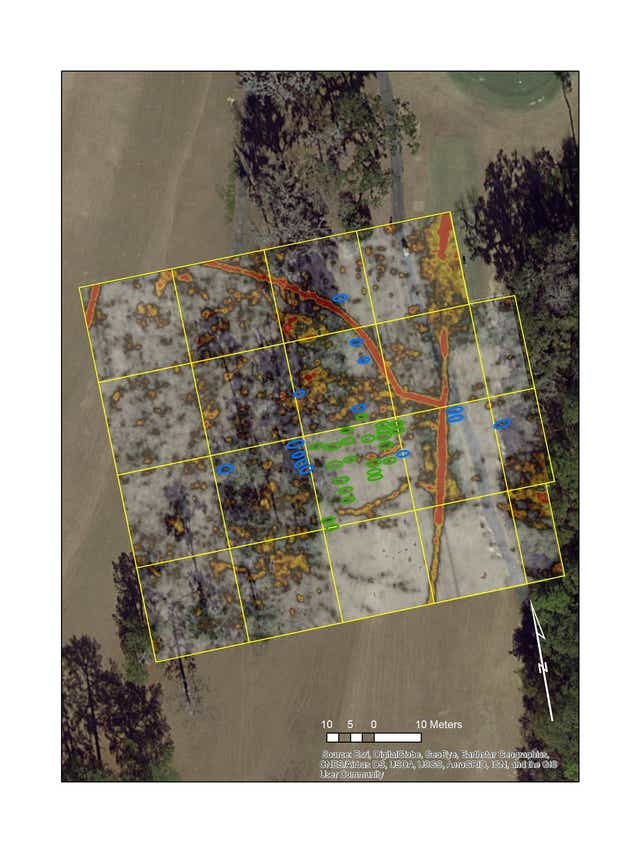

Earlier this month, after weeks of scanning 7,000 square meters of the golf course using ground-penetrating radar and two cadaver-sniffing dogs, Shanks issued his preliminary conclusion: the subsurface anomalies at the country club are indeed graves. The discovery of Shanks’ findings were significant because so many slave cemeteries are unaccounted for.

“It’s a really serious problem,” Shanks said to The Guardian.com. “It’s not just a Florida problem. It’s really a problem across the south-east.”

However, this issue is hardly a new one, as two decades ago, a Florida state task force estimated that there could be as many as 1,500 unmarked and abandoned slave or African American cemeteries across the state. Some Florida lawmakers want to establish a new task force to address the matter.

“We want to identify covered-up graves that have been built upon, or destroyed, or obliterated from history,” said state senator Darryl Rouson, whose district lies in the Tampa Bay area. “Once identified, we’d like to do some type of memorial for those souls.”

To bring about recognition of the cemeteries, there have been national discussions about establishing an African American Burial Grounds Network. Work is also underway on a national database to record the burial sites for enslaved Americans.

As property, slaves were not accorded dignity in life nor in death, said Jonathan Lammers, a historian who drafted a report on the Houstoun property.

“They were nameless on census records, and they are nameless and unremembered in death,” he said.

Despite the scores of plantations that once existed in Leon county, there are only a handful of known slave burial sites. And, it is anticipated that each plantation would have had a cemetery for its enslaved people.

“It’s safe to say that there are thousands upon thousands of these graves in Leon county,” Lammers said, “and hundreds and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, across the south-east that remain unknown today.”

For the time being, at the Capital City Country Club, there are no plans to exhume or disturb any of the rediscovered remains, and exactly how the site will be memorialized is still up for discussion. Hollinger, for one, told The Guardian.com that he wants to reroute golf carts and fence off the area so golfers won’t tread over the graves. He also proposes a small memorial that will recount, he said, the unvarnished history of the property – including how it profited from the labor of slaves.

He doesn’t want the history of these graves “to be prettied up” or romanticized. “I want us to be accurate and truthful in the story we tell.”