(By O.A. Scott)

Whatever you think about the past and future of what used to be called “race relations” — white supremacy and the resistance to it, in plainer English — this movie will make you think again, and may even change your mind. Though its principal figure, the novelist, playwright and essayist James Baldwin, is a man who has been dead for nearly 30 years, you would be hard-pressed to find a movie that speaks to the present moment with greater clarity and force, insisting on uncomfortable truths and drawing stark lessons from the shadows of history.

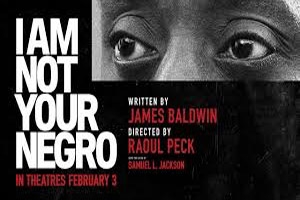

To call “I Am Not Your Negro” a movie about James Baldwin would be to understate Mr. Peck’s achievement. It’s more of a posthumous collaboration, an uncanny and thrilling communion between the filmmaker — whose previous work includes both a documentary and a narrative feature about the Congolese anti-colonialist leader Patrice Lumumba — and his subject. The voice-over narration (read by Samuel L. Jackson) is entirely drawn from Baldwin’s work. Much of it comes from notes and letters written in the mid-1970s, when Baldwin was somewhat reluctantly sketching out a book, never to be completed, about the lives and deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Reflections on those men (all of whom Baldwin knew well) and their legacies are interspersed with passages from other books and essays, notably “The Devil Finds Work,” Baldwin’s 1976 meditation on race, Hollywood and the mythology of white innocence. His published and unpublished words — some of the most powerful and penetrating ever assembled on the tortured subject of American identity — accompany images from old talk shows and news reports, from classic movies and from our own decidedly non-post-racial present.

Reflections on those men (all of whom Baldwin knew well) and their legacies are interspersed with passages from other books and essays, notably “The Devil Finds Work,” Baldwin’s 1976 meditation on race, Hollywood and the mythology of white innocence. His published and unpublished words — some of the most powerful and penetrating ever assembled on the tortured subject of American identity — accompany images from old talk shows and news reports, from classic movies and from our own decidedly non-post-racial present.

Baldwin could not have known about Ferguson and Black Lives Matter, about the presidency of Barack Obama and the recrudescence of white nationalism in its wake, but in a sense he explained it all in advance. He understood the deep, contradictory patterns of our history, and articulated, with a passion and clarity that few others have matched, the psychological dimensions of racial conflict: the suppression of black humanity under slavery and Jim Crow and the insistence on it in African-American politics and art; the dialectic of guilt and rage, forgiveness and denial that distorts relations between black and white citizens in the North as well as the South; the lengths that white people will go to wash themselves clean of their complicity in oppression.

Baldwin is a double character in Mr. Peck’s film. The elegance and gravity of his formal prose, and the gravelly authority of Mr. Jackson’s voice, stand in contrast to his quicksilver on-camera presence as a lecturer and television guest. In his skinny tie and narrow suit, an omnipresent cigarette between his fingers, he imports a touch of midcentury intellectual cool into our overheated, anti-intellectual media moment.

A former child preacher, he remained a natural, if somewhat reluctant, performer — a master of the heavy sigh, the raised eyebrow and the rhetorical flourish. At one point, on “The Dick Cavett Show,” Baldwin tangles with Paul Weiss, a Yale philosophy professor who scolds him for dwelling so much on racial issues. The initial spectacle of mediocrity condescending to genius is painful, but the subsequent triumph of self-taught brilliance over credentialed ignorance is thrilling to witness.

In that exchange, as in a speech for an audience of British university students, you are aware of Baldwin’s profound weariness. He must explain himself — and also his country — again and again, with what must have been sorely tested patience. When the students erupt in a standing ovation at the end of his remarks, Baldwin looks surprised, even flustered. You glimpse an aspect of his personality that was often evident in his writing: the vulnerable, bright, ambitious man thrust into a public role that was not always comfortable.

“I want to be an honest man and a good writer,” he wrote early in his career, in the introductory note to his first collection of essays, “Notes of a Native Son.” The disarming, intimate candor of that statement characterized much of what would follow, as would a reckoning with the difficulties of living up to such apparently straightforward aspirations. Without sliding into confessional bathos, his voice was always personal and frank, creating in the reader a feeling of complicity, of shared knowledge and knowing humor.

“I Am Not Your Negro” reproduces and redoubles this effect. It doesn’t just make you aware of Baldwin, or hold him up as a figure to be admired from a distance. You feel entirely in his presence, hanging on his every word, following the implications of his ideas as they travel from his experience to yours. At the end of the movie, you are convinced that you know him. And, more important, that he knows you. To read Baldwin is to be read by him, to feel the glow of his affection, the sting of his scorn, the weight of his disappointment, the gift of his trust.

Recounting his visits to the South, where he reported on the civil rights movement and the murderous white response to it, Baldwin modestly described himself as a witness, a watchful presence on the sidelines of tragedy and heroism, an outsider by virtue of his Northern origins, his sexuality and his alienation from the Christianity of his childhood. But he was also a prophet, able to see the truths revealed by the contingent, complicated actions of ordinary people on both sides of the conflict. This is not to say that he transcended the struggle or detached himself from it. On the contrary, he demonstrated that writing well and thinking clearly are manifestations of commitment, and that irony, skepticism and a ruthless critical spirit are necessary tools for effective moral and political action.

Recounting his visits to the South, where he reported on the civil rights movement and the murderous white response to it, Baldwin modestly described himself as a witness, a watchful presence on the sidelines of tragedy and heroism, an outsider by virtue of his Northern origins, his sexuality and his alienation from the Christianity of his childhood. But he was also a prophet, able to see the truths revealed by the contingent, complicated actions of ordinary people on both sides of the conflict. This is not to say that he transcended the struggle or detached himself from it. On the contrary, he demonstrated that writing well and thinking clearly are manifestations of commitment, and that irony, skepticism and a ruthless critical spirit are necessary tools for effective moral and political action.