Muhammad Ali, who has died aged 74, was acclaimed by many as the greatest world heavyweight boxing champion the world has ever seen. He was certainly the most charismatic boxer. His courage inside and outside the ring and his verbal taunting of opponents were legendary, as were his commitment to justice and his efforts for the sick and underprivileged.

Three times world champion, Ali harnessed his fame in the ring to causes outside it. He was a convert to Islam and the personification of Black Pride. He anticipated the anti-Vietnam war movement of the 1960s by refusing to join the armed forces.

He made goodwill missions to Afghanistan and North Korea, delivered medical supplies to an embargoed Cuba, and travelled to Iraq to secure the release of 15 US hostages shortly before the first Gulf war. Repellent though he found many aspects of US foreign policy – and repellent as the establishment found him when in 1967 it banned him from the ring for three years for refusing the draft – the nation embraced Ali as time passed, realising his unique ambassadorial value. In 2005, he received his country’s highest civilian honour, the presidential medal of freedom, from George W Bush, an incumbent whose views he must have detested.

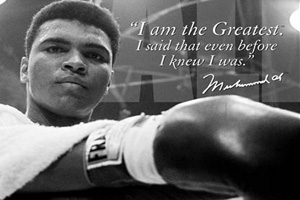

But it all stemmed from boxing. His matchless magnificence, the self-proclaimed “greatness”, was invented early as a cheery prizefighter’s publicity stunt. It was a greatness that was to balloon and achieve near-universal acceptance as he became acknowledged as a beacon not only for downtrodden African Americans but for global Islam as well, not to mention the anti-war movement or poverty in developing countries. In the middle of press conferences, reporters would earnestly ask him about solving the Palestine problem, or if he could have a quiet word with Moscow about President Ronald Reagan’s star wars programme. Ali was a rebel with a cause – lots of them.

He played the sovereign to the hilt. He played the victim. He played the clown. He played the camera. But, above all, he played the sport. He was the best heavyweight boxer there had ever been since the Marquess of Queensberry set down his rules in 1867, undeniably the best since Kid Cain KO’ed Sugar Ray Abel. First as Cassius Clay, then as Ali, this remarkable boxer totally reset the marks, utterly changed all inviolate techniques and tenets. Four years after winning the light-heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Olympic games in Rome, he won the undisputed professional world heavyweight championship, taking on all comers. He was to regain the title twice, an achievement that remains unmatched. His career in the professional ring spanned an astonishing 21 years. Of 61 contests, he lost only five, four of them when he was long past his majestic best. Thirty-seven victories were knockouts.

Read more at The Guardian.com