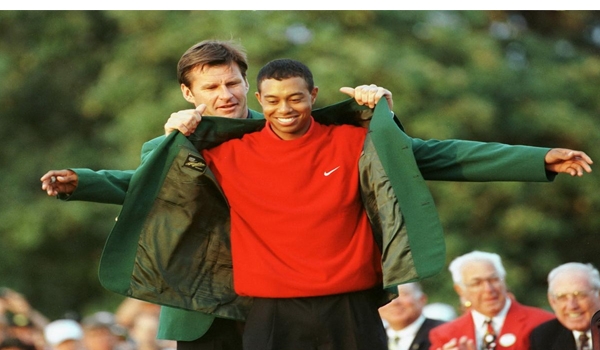

Tiger Woods as he is receiving the 1997 Masters tournament’s green jacket from the 1996 Masters champion, Nick Faldo.

(by Pete McDaniel)

I’ve recounted the final round of the 1997 Masters many times, and I never tire of it.

Yes, that round. The one of such historical resonance that it lifted an entire race of underserved and unrecognized Americans from the back roads of golf to the highly visible super highways of the sport. The one that punctuated Tiger Woods’ 12-stroke moonwalk to victory among the Georgia pines. The one where the 21-year-old fist pumped his way into the consciousness of 5-year-olds and graybeards alike—an exclamation point on a performance that heralded his arrival as golf’s transcendent player. If you don’t believe me, feel free to Google it. You’ll find my version of the story on every medium.

I walked every hole with Tiger that week because it was not only my job but my pleasure. I quietly reveled in his superiority as I trekked among the “patrons’’ outside the ropes. I didn’t even mind the Masters’ strict rules requiring print media to cover the “toonament’’—that’s how they pronounce it in Augusta— from outside the ropes when every other event allowed credentialed media inside them. Just another power play by the green jackets in the Masters control-room, I reasoned.

I was Tiger’s ghostwriter, loyal to a fault co-author of his father’s soon-to-be-released bestseller “Training A Tiger,’’ proving capable of walking the thin line between journalist and cheerleader. I was also on a personal mission to justify the New York Times Companies’ Affirmative Action-induced decision to give me a shot at Golf World and later Golf Digest. Just like Satchel Paige (legendary pitcher who at the age of 42 signed with Major League Baseball’s Cleveland Indians in 1948), Fritz Pollard (the NFL’s first black quarterback) and every other groundbreaker, I was attempting to prove that more than WASPs had the necessities to successfully handle positions considered cerebrally demanding.

I don’t mean to compare my impact on golf writing with the accomplishments of legends, but I’m certain had my mama lived to see her baby boy’s rise in the industry, she would have been mighty proud. If you read the introduction to Uneven Lies: The Heroic Story of African Americans in Golf, you know that her approval was all that mattered to me. That said, this is not about me but a seminal moment in the history of the game—a moment of particular import on the 20th anniversary of a final round that ushered in Tigermania.

The anticlimactic (Tiger led by nine after 54 holes) final round was part coronation, part vindication and part resurrection. Lee Elder, the first black invited to the Masters (in 1975) was in Tiger’s gallery, having been delayed by a burly highway patrolman as Elder raced along I-20 from Atlanta to Augusta that morning. Perhaps Tiger’s victory took a little bit of the sting out of his speeding ticket.

Charlie Sifford, Tiger’s “adopted’’ grandfather, was there in spirit, too. Sifford, who should have been the first black invited to play in the Masters except for the committee’s continual relocation of the goal posts, encouraged young Tiger via telegrams. The ghosts of pioneers Bill Spiller and Teddy Rhodes, like Sifford players worthy of an invite that never came, were there, too. Their muted shouts of joy could be distinguished from the others whispering among the pines by the discerning ear. I certainly heard them.

Colin Montgomerie, the crotchety Scot who had a front row seat to Tiger’s mastery of Augusta National in round three, accurately predicted that Tiger would increase his margin of victory on Sunday. Just about everyone who had been paying attention believed the same. As for the protagonist himself, certain victory was the farthest thing from his mind.

Back at the rental house that served as Team Tiger’s compound that week, restlessness chased Tiger out into the night air. On his way back to his room, he spotted a light on in Earl Woods’ bedroom. So he had a little talk with “Pop’’ not so much for fatherly advice but more for self-assurance. Father told son to expect Sunday to be a most difficult day as he sought to become the Masters’ youngest champion. He also assured his progeny that he was well equipped to handle the moment.

When I arrived at the Woods house on Sunday morning to check on Earl, which had been my daily ritual, Earl was in relax mode as if the deal had already been signed, sealed and delivered. I later discovered that he was conserving his energy in order to fulfill the promise of being at the 18th green with a big bear hug for his son after the round. Still pale and a little weak as he recovered from a recent second heart bypass surgery, Earl would nap between needles to yours truly. On this morning, however, he appeared more introspective.

Earl was a complicated dude. One minute he was bombastic; the next humble pie. He was a very intelligent man, who knew a little about a lot but everything about one thing: how to rear the youngest of his four children. Earl knew his son would handle the final-round challenge on the grandest stage in golf. Of course, he was right.

When Tiger holed out to complete the 12-stroke victory, Earl was right there greenside to bear hug his way into Masters lore.

Tiger’s mom, Kultida, has teased me many times about the ravages of time. “You can’t fool Mother Nature,’’ she chides. Well, my diminished memory is proof positive of that sound bite. However, I will never forget walking up the 18th fairway outside the ropes and looking toward the massive clubhouse, where club employees had gathered along its veranda overlooking the 18th green.

The mostly black faces were smiling. For years they had faded into the background like furnishings or artwork at the historic club. Not on this day, though. On this day, they openly celebrated the long-awaited dawn of a new era—one in which they would no longer be invisible men and women. Thanks to a young man who looked like them.

Pete McDaniel is a veteran golf writer and best-selling author. His blogs and books are available at petemcdaniel.com Comments on this topic may be emailed directly to Pete at: gdmcd@aol.com