By Pete McDaniel

The tall drink of water had an obvious limp that didn’t in the slightest diminish his style and grace. Other than that, Charlie Owens looked like a professional golfer in his red sans-a-belt slacks, matching shirt, shoes and visor.

He was “the man from Florida.’’ That was the advance on Charlie, although it didn’t appear to do him justice.

It was around 1969 or ‘70, and the Skyview Open was being contested at the Asheville (NC) Municipal. The chittlin’ circuit event was the reason that Owens and a few dozen other mostly black pros had descended on the small town tucked in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The 54-hole tournament had been a mainstay on the North American Golf Association Tour for several years. Along with five or six other stops from Eufaula, Al., to the south up the East Coast to Washington D.C., Asheville was penciled in by every alternative tour hopeful worth his salt. Some would schedule vacation around the various events. Others would quit their jobs altogether to chase their dream another season.

RELATED STORY: 2016 National Black Golf & Jazz Pioneers Tournament & Achievement Awards Swings With Legends in New Orleans, LA

RELATED STORY: 2016 National Black Golf & Jazz Pioneers Tournament & Achievement Awards Swings With Legends in New Orleans, LA

For some players, like Chuck and Jim Thorpe, Jim Dent, George Johnson and Nate Starks (among others), the mini-tour proved a stepping stone to the PGA Tour. For others, it was a tradition where wannabes gathered to hustle the uninitiated and enjoy the substantial hospitality of local “golf” enthusiasts, many of whom didn’t know a pitching wedge from a potato wedge, but they sure liked the way those sans-a-belts fit.

As a high school golfer with above average skills developed at the Asheville Muny, the only course in the area where a black caddie could grind out a decent game, I usually played in the amateur division of the Skyview. However, that year I decided to caddie for the defending champion, one James Black from Charlotte, NC.

I actually stole Black’s bag from the younger brother of a classmate. He had caddied for Black the year before, but I got wind of Black’s early arrival and raced to the course to secure the job.

I thought he was the best player I’d ever seen in person. Better than local stud Harry Jeter. Even better than Lee Elder or Charlie Sifford, who I had only seen on TV.

RELATED STORY: James Black, In The Zone

RELATED STORY: James Black, In The Zone

I just had to share my course knowledge and superior green reading ability with him. I knew every break on every green at the course I had played since I was 12. With me on the bag, he was a shoo-in repeat champ.

Some of the other caddies jockeyed for position when Charlie drove up in his shiny Cadillac. I don’t remember who he chose, but I do recall being glad I was on Black’s bag and not his.

Charlie Owens, who used the same cross-handed grip from start to finish of his playing days, could be quite surly in the best of times and downright ornery in the worst of them. We used to call players with such bipolarity caddie killers.

Like most years, the tournament was hotly contested. Red numbers aplenty as the best black players in the land not named Sifford or Elder or Brown (as in Pete Brown) scorched the diminutive Donald Ross design. At the end of regulation, two players were tied—James Black and Charlie Owens.

Black birdied the first playoff hole to edge Owens. I received the princely sum of $100 for three days work and looked forward to Black calling me “Pally’’ again the next year.

Black and the other troubadours traveled west to Knoxville. I’m sure Charlie went, too.

RELATED STORY: Golfing Pioneer Charlie Owens Dies at 85 in Winter Haven, FL

RELATED STORY: Golfing Pioneer Charlie Owens Dies at 85 in Winter Haven, FL

A year or two later (1971), Charlie won the Asheville Kemper Open, a satellite tour event at Etowah Valley GC, a course I played dozens of times when I was Sports Editor of the Hendersonville Times-News. Sometime later his name appeared in the agate type among the other also-rans in PGA Tour events.

He never won on the big tour, but he did find success on the senior circuit. He also either invented or popularized (depending upon who one believes) the long putter. And he championed the cause for the use of carts by seniors.

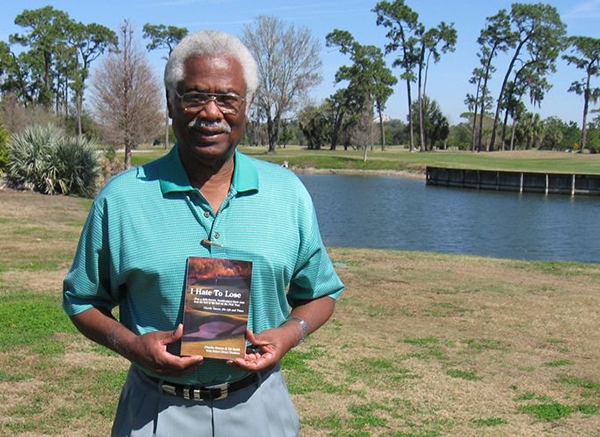

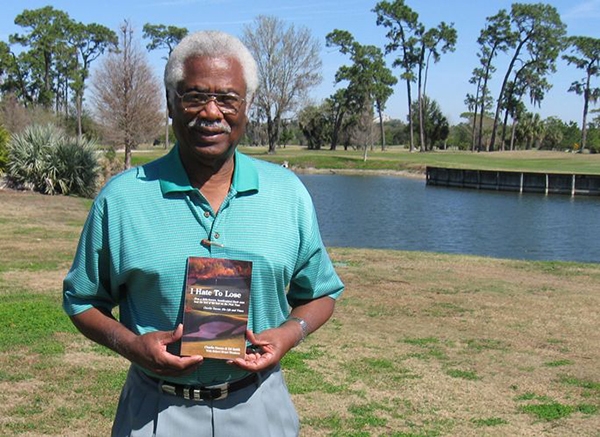

Charlie Owens, the retired head pro at Tampa’s Rogers Park, holds a copy of his book, “I Hate To Lose,” confronted racism, injustice and pain on and off the golf course. Photo: TampaBay.com

The latter didn’t endear Charlie to the Tour brass, but he didn’t give a damn. He loved a fight. And he won more often than not.

Many years later Charlie and I were reunited when I interviewed him for Uneven Lies: The Heroic Story of African Americans in Golf. He had mellowed, a little. He would become much kinder and gentler as a respected retiree at Rogers Park GC in Tampa, where he once served as head pro.

Charlie loved interacting with the other graybeards at Rogers Park and the young dreamers on the Advocates Pro Tour. But mostly Charlie loved overcoming adversity, like when he managed to make it to the big time despite a fused knee, the result of a failed correction of an injury he suffered as a paratrooper in the U.S. Army.

Like when the yips threatened to end his career, but the long putter revived it.

Charlie recently passed in his native Winter Haven, Fl. He was 85. I was a part of his life for only a short while, but his friendship and respect had a positive impact on mine.

Pete McDaniel is a veteran golf writer and best-selling author. His blogs and books are available at petemcdaniel.com

[fbcomments]

Comments on this topic may be emailed directly to Pete at: gdmcd@aol.com