February 26, 2021 | BY AAGD STAFF

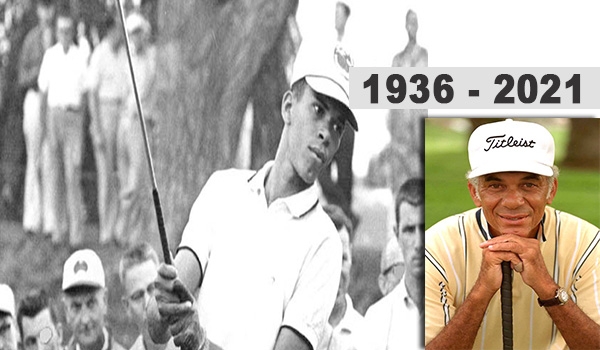

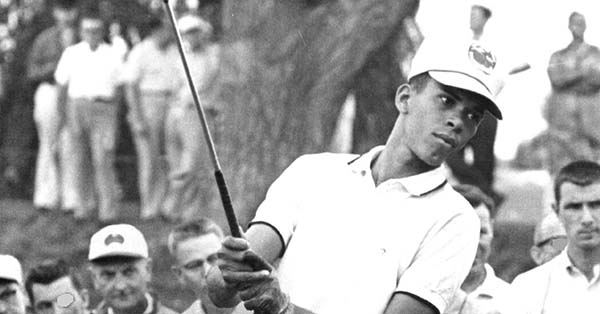

The first Black man to win a major U.S. golf tournament, William “Bill” Wright, a Western Washington University Hall of Famer, died Friday in Los Angeles at 84, the school announced his death in a release.

Wright was born in Kansas City, Mo., in 1936. He only child of Bob and Madeline Wright. His father was a postman and his mother a schoolteacher. The family moved to Portland, Ore., when he was 12 and later to Seattle, where Wright was introduced to the game by his father at Jefferson Park, the same municipal course where future Masters champion Fred Couples honed his skills.

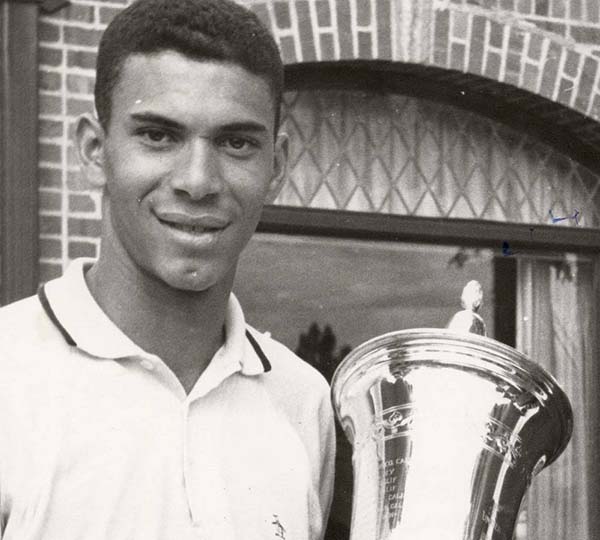

On July 18, 1959, Wright became the first Black to win a tournament conducted by the United States Golf Association, when he captured the U.S. Amateur Public Links title at the Wellshire Golf Course near Denver. At the time, Wright was 23-years-old and a senior at Western Washington University.

Although he was one of the top golfers in the state, neither of the two major Division I colleges in town – the University of Washington and Seattle University – offered him a scholarship.

His college senior year would gain even more momentum when Wright claimed medalist honors at the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) National Tournament. His accomplishment earned him induction into the WWU Athletics Hall of Fame (1968), only one of the first seven former students athletes to be enshrined. For this feat, Wright was named Golfer of the Century (1999) by the school, according to the release.

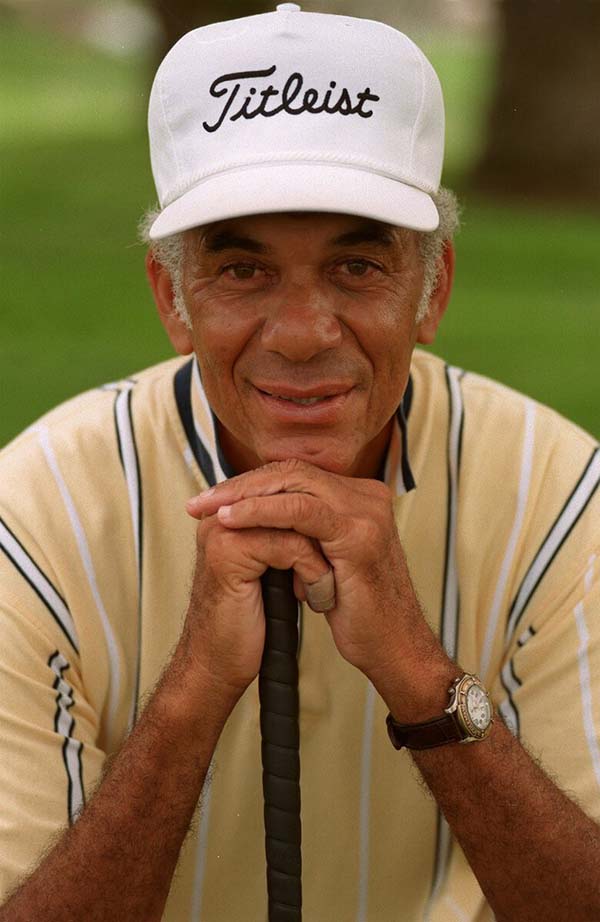

A legendary representative of Western Washington University, Wright had a top-notch personality that matched his athletic abilities. He was known as a “wonderful human being,” said WWW Director of Athletics Steve Card in the release. Card is also a former Viking Golf Coach.

“He impacted the world by breaking the color line in American golf, but beyond that he was an incredible person who touched a lot of people in so many ways.”

After graduating from Western he made a run for the Public Links title (1961) in Michigan, but lost in the semifinals. After turning pro in the early 1960s, he was unable to play full-time on the PGA Tour due to lack of finances. Wright did compete in the 1966 U.S. Open and managed to later play in five U.S. Senior Opens, according to the release.

Wright earned many distinctions and honors during his lifetime. He has been enshrined in the USGA Museum in Liberty Corner, New Jersey, and is a member of the Pacific Northwest Golf Association Hall of Fame and African American Golfers Hall of Fame.

To earn income, Wright taught elementary school in Los Angeles’ Watts district for nine years, and continued even during the 1965 riots, according to the release. Additional monies were earned by detailing cars, before he successfully acquiared a leasing business and dealership ownership in Pasadena.

Wright was able to work in the golf industry and served as the golf professional at The Lakes Golf Course in El Segundo, California, for 25 years. While there, he operated a golf club repair shop at the course for nine years, until 2009.

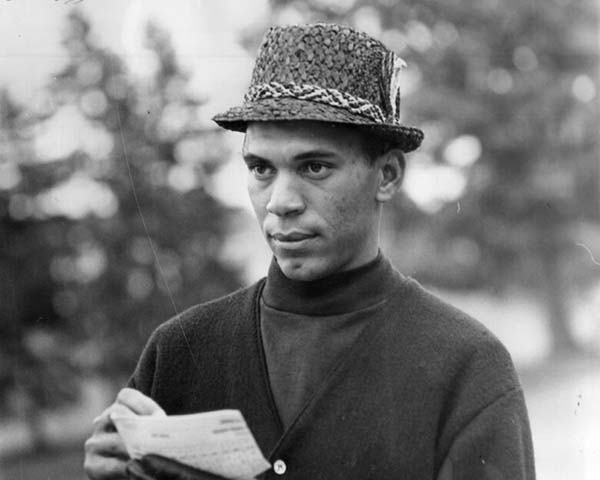

Wright was not allowed to carry a golf handicap before arriving at WWU in the 1950s. He was unable to play in men’s club events or even in the Seattle City Amateur because of being a Black man, according to the release. It was not until 1954 that Wright convinced the Seattle City Amateur tournament administrator to allow him and his father to compete in the tournament — Wright finished first and his father was third, and more importantly, doors began to open allowing Wright to play in more tournaments.

Wright was an active athlete and indulged in many other sports outside of golf including basketball. But the color of his skin was a continued hindrance. In fact, Wright spent one quarter of the school year at the University of Washington, before then Husky basketball coach Tippy Dye told him he did not want to have the school’s first Black player on his team, the WWU release states.

In a close friendship that Wright developed with Dean C.W. “Bill” McDonald, Wright decided to transfer to Western Washington College of Education. McDonald was a former UW player who had served as Western’s basketball coach until 1955. It was a good move for both McDonald and Wright, as Wright helped the Viking basketball team to a 14-8 record, averaged 12.5 points per game, and earned second-team all-Evergreen Conference honors during the 1958-59 season.

“We have lost a hero, but the advice and lessons that Bill provided will have a lasting impact for generations to come,” Card said in the release. “The term ‘great’ or ‘greatest’ gets tossed around loosely in the sports world. Bill Wright was a GREAT human being. For me personally, calling him my friend, is one of my life’s greatest blessings.

“My heart goes out to his lovely wife, Ceta, during this difficult time.”